This weekend I was at a seminar with no-gi submission wrestling/Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu wizard Eddie Bravo.

He’s a pretty cool dude, as reflected both by his cool name and by the system he founded (10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu), which is probably somewhere along the lines of how I imagine my system could look like if I were to “create” my own methodology for teaching/systematizing Karate.

In other words, awesome.

Just to give you an idea of the genius in 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu, here’s an example of a flowchart for the grappling position known as the Twister. Here’s one for the Rubber Guard. Man, I love his creative naming. Also, he strongly advocates stuff like feinting “chops to the balls”, in order to elicit the natural predetermined flinch reflex (man’s weakness!) before attempting your ground submission move (what we in Karate generally label ne-waza, kansetsu-waza). Good stuff.

As you can probably imagine, Eddie Bravo has pretty much revolutionized the way people teach, analyze, interpret and practise Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and no-gi submission grappling. Especially for MMA.

And the best part of it all?

He has a fat KARATE patch on his pants (look where his hand is)!

Here, I even cropped it out for you:

What’s up with that?

No, seriously, what the fudge is happening here? First we had MMA fighter Lyoto Machida KO’ing the legendary UFC Hall of Famer Randy Couture earlier this weekend at UFC 129 – with the KARATE jump kick from kata Kanku Dai (he even said so!) – which then Steven Seagal somehow managed to take credit for (say what?), and now we have MMA groundwork emperor Eddie Bravo sporting a shiny orange KARATE patch on his blue gi pants?

Something definitely is up. Crazy weekend for sure.

But let’s leave it at that for now.

Because what I really wanted to write about today is a principle of Karate which is very important both for regular good ol’ stand-up fighting (long range), the clinch/elbow/knee/takedown range (close range) as well as for traditional (ground-based) grappling.

I call it the 4 Point Principle.

And the reason I wrote about my grappling weekend in the intro was because all this ne-waza stuff reminded me of how important spinal alignment, leverage, correct angles and (core) control truly is in close-quarter combat.

Kata, kihon, kumite… bunkai.

My friends, if you don’t have your 4 Point Principle under control, then you’re knee-deep in it.

(“It” being a brown smelly substance.)

That’s why every Karate-ka truly needs to master the 4 Point Principle.

So what is it then? What is this allegedly super secret, ultra awesome, highly important principle that we all need to master? Don’t worry. I’ll tell you. That’s what this article is about. And it’s neither particularily secret nor difficult. Just very important.

Also, it requires some thought.

And most of all practise.

So let’s quickly look at three practical examples of the 4 Point Principle (4PP) how it is applied in some different scenarios and how you can test it yourself.

The 4PP: Application Example #1

So, for these pics I’ve recruited my loyal slav… “sempai” Tobias-san. It wasn’t that hard. I just dangled a black belt in front of his eyes and my words were his law. Anyway, bribes aside, as you can see on the above picture the four main points that we’re going to talk about in this principle is left shoulder, right shoulder, left hip, right hip.

These are the four points that we generally want aligned in all planes when executing techniques (horizontal, vertical).

These are the four golden points.

To further clarify what I mean, let’s use a sokutsu-dachi, soto-uke (yoko-uke) as an example. As seen in kata such as Kusanku/Kanku, Bassai etc.:

See this example?

Find the problem.

While Tobias-san admitted it felt pretty weird to position himself like this, many people can be seen in pretty similar positions during kata or kihon practise in dojos all over the world. Often even in kata tournaments, effectively proving to the onlookers how little understanding of their bodies they actually have (in a sport where showing correct understanding of the execution of techniques supposedly is the ultimate goal).

Found the problem with the above pic yet?

Let me help you: The hips are “facing” forward, while the shoulders are rotated back. Meaning, the upper half of the body is effectively left unconnected to the lower part of the body, resulting in a less than optimal execution of technique (let’s just ignore the feet for now). In other words, the four points (shoulder, shoulder, hip, hip) are not aligned. Which sucks.

Because they need to be.

At all times.

In all planes.

Let’s look at what the opposite scenario would look like:

Here we instead have the hips turned back, but the shoulders facing front.

Or at least that’s what the position was supposed to look like, but it was so unnatural that this was the best Tobias-san could muster.

(Do I smell a degradation coming?)

Anyhow, the same idea applies. Hips and shoulders are not fully aligned. Result = bad Karate. But let’s sharply turn our attention away from these horrible images and instead look at something more worthy of our quality demanding eyes.

Aah… harmony.

Shoulders and hips are now properly aligned.

Or at least we’d like to think so. Because like previously mentioned, we’re working in three dimensions here. All planes. 360 degrees. Which mans that although your hips might be straight below your shoulders, they can still wobble in the other direction.

Look at this nekoashi-dachi, shuto-uke for instance:

See what I mean?

Although the shoulders and hips are pretty much aligned, something is wrong. In this case, Tobias-san’s right hip point is not on the same plane as his left hip point, and the same goes for his shoulders. One is above/below the other, resulting in our spinal alignment being compromised. This is very common. And very bad. Because we all know a straight tree grows the tallest.

The same goes for the opposite scenario:

My eyes. Bleeding. Are.

No, but seriously, you get the point. Not only does the lower plane (hips) need to be in line with the higher plane (shoulders), but the individual points of each plane need to be aligned with each other. That’s the general idea of the 4 Point Principle.

And here’s a fun way to test it: Have everyone in your Karate class do their favorite kata, or whatever movements they feel like. No counting, no nothing. Own pace. Your job is to walk around the dojo, and occasionally clap your hands. Whenever you clap, everybody needs to freeze in whatever move/position they are in. Now look around. Everyone who is not having their four points in alignment (some will, but most will probably not…) gets a tap on the shoulder from you and needs to perform three push-ups, or whatever, as “punishment” for having crappy technique.

Or you can just skip that punishment part, maybe I’m a little sadistic.

But it’s a good way to sneak in extra push-ups!

Anyways, that was a very brief breakdown of the first example in how the 4 Point Principle is understood, applied and practised.

Here’s the second:

The 4PP: Application Example #2

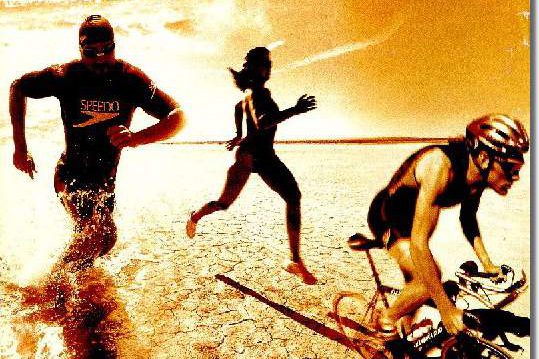

So you are in the clinch zone this time, doing some standing pushing/shoving/grappling with your opponent, when you finally decide to take him/her down. Problem is, you probably can’t. You will struggle. It will become a muscle thing.

Why? Because you both have equally good balance. So, in order to break your opponents balance (kuzushi), you actually need to break their 4 Point alignment. The more the better.

It’s as “easy” as that.

(Obviously while keeping your own alignment intact.)

Here, let’s use the traditional o-soto-gari sweep as an example:

Look at the four points of the principle in question.

Look at the four points of the principle in question.

In this wonderful drawing, they are almost perfectly misaligned, all of them. This is probably the best you can do with a o-soto-gari before tripping the opponent; which is pretty easy once you’ve come this far.

Awesomeness redefined.

Another example:

Here’s some random pic I found on Google. But it works.

In this case, the breaking of your opponent’s alignment is not achieved by pulling/pushing with your arms, but with an atemi. That is, a strike.

But it might as well be a punch, chop, kick, or something else which elicits a defensive reaction in the opponent, making him misalign himself to your advantage. Joint locks will have the same effect.

Takedown from here is a piece of cake.

Since I trust you get the gist of what I’m saying, let’s jump to the last scenario; the ground game.

Oh, I almost forgot! How do you test this? By doing standing randori (Judo sparring), but with punches, pinches, kicks, chokes and joint locks of course. Mix it up with some of that dirty Karate stuff! Very fun and interesting, for sure.

The 4PP: Application Example #3

Okay, last part.

Ne-waza.

Ground techniques.

Here I’ve successfully recruited Tobias-san again. And although general ground-based grappling isn’t a big part of Karate (you’d best avoid going there!), this principle is too important to overlook. Even if you never wrestle. Also, it works equally well if you pin somebody to a wall… so I guess that’s the take home if you’re one of those who don’t like ne-waza.

Anyhow, see the four points we’ve been talking about here?

Those are the main points you want to control at all times if you wish to lock down your opponent. The more the merrier.

Only controlling the hip points will result in failure is your opponent simply performs a sit-up, while only controlling the shoulder points will result in failure if your opponent decides to do a kip-up/bridge.

So, control the four points as much as you can, and if you can only control two points then for Funakoshi’s sake do it diagonally for maximum effect with minimum effort (aka the “Judo principle” or seiryoku zenyo). Three is good too. One is not that good. Two on the same side can work if you’re skilled.

Of course, the same goes if you are the one being pinned to the ground.

I mean, if you don’t know a certain technique for escaping/reversing a position, be sure to at least release as many of the four points you can, to maximize your chances of shaking free. Anybody can do that, as long as they put some thought into it.

And how do you test this? Well, do some ne-waza randori (ground-based free sparring), keeping in mind the 4 Point Principle both in yourself and your opponent at all times. Sprinkle some grimey, nasty Karate techniques on top (chop to the balls, as Eddie Bravo advocates) and you have a deadly dish best served cold.

And that was the last scenario I planned to write about in this article on the general theory and application of the 4 Point Principle.

Thanks for reading this far.

Hey, by the way, I just realized you could easily make this into a whole weekend seminar with all kinds of awesome charts, PowerPoint presentations, postural exercises, pilates moves, the three above scenarios/fighting ranges with various accompanying drills/exercises, DVD’s, books, folders… Dang it! And I just gave it all away for free, just like that!

I guess that’s just how I roll.

If any of you nifty senseis out there do decide to do that, you know where my Paypal account is located at. Thanks. I appreciate it. Love you too.

(Or just buy some friggin t-shirts already!)

Now go get your 4 Point Principle on!

5 Comments